When was the last time you eagerly clicked on a voucher code site, only to be disappointed by the actual offer? If you’ve felt that frustration, you’re not alone. Coam’s recent deep dive into the world of voucher codes reveals a widespread issue that’s likely even more significant than you imagined.

In an extensive study involving over 4,500 offers across 60 “brand + voucher code” searches, we uncovered that 92% of meta titles that reference individual offers, fail to fully disclose the details and terms of that offer.

The impact on a consumer’s user experience is obvious.. In highlighting this issue we’re not calling out specific publishers or advertisers but instead putting ourselves in the shoes of a consumer when shopping through voucher code sites. The screenshots and examples used are purely for illustrative purposes.

What is meta data?

Meta data in the context of online shopping refers to information embedded in a webpage’s HTML that helps search engines understand the content. Meta titles (title tags) are brief, descriptive titles that appear in search results, influencing whether online shoppers click on that particular link.

Meta descriptions are short summaries displayed beneath the meta titles in search results, offering a concise overview of the page’s content to entice clicks. Both elements are crucial for attracting online shoppers, improving visibility, and driving traffic to boost sales.

Real Examples, Real Problems

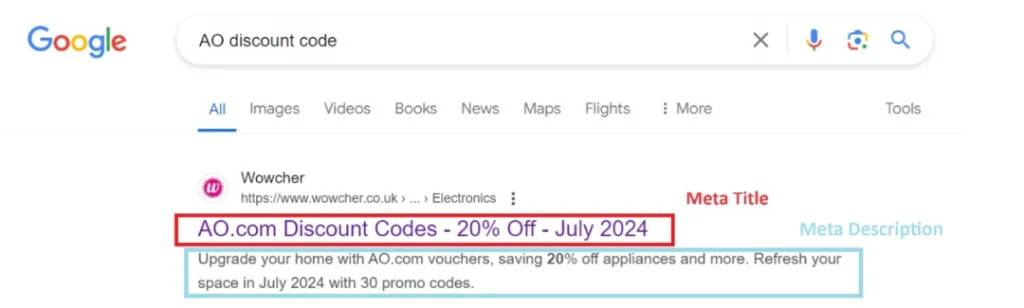

When you search for a voucher code relating to a particular brand, 78% of those searches result in meta page titles that reference a specific offer (either in the meta title or in the meta description). In the example below you can see that a meta title is the headline of a search result and the meta description is the short summary underneath the headline:

It is common practice to optimise meta data for search engines but sometimes this can mean that the offers we see do not always match the offers available.

We can also split the nature of this disconnect into two distinct types:

Being vague with the true nature of the offer happens 92% of the time:

The first discernible difference between the meta titles and the actual offers consumers see on a voucher website are the offer terms and conditions.

Meta titles are intentionally vague to make offers sound more attractive and appealing than they really are. It is easy to see why the experience that the first encounter a consumer has on their journey to potential savings that don’t exist can be misleading and confusing.

Let’s look at some specific examples to help bring this to life:

| Meta Title | Actual Offer |

| Nike discount code 25% OFF in May 2024 | Become a Nike member to save 25% off on your birthday |

| Jet2 Discount Codes | 20% Off May 2024 Promo Codes | 20% off in-flight meals only OR 20% off the cost of checked bags |

| Currys Discount Codes – Verified 30% off May | 30% off Selected Watch Straps with Samsung Galaxy Watch4 Orders at Currys |

| TUI Discount Code 2024/2025: £300 OFF in May | Up to £300 off Holidays to Turkey at TUI |

| Iceland Discount Codes for May 2024 ✓ 50% Off Your Order + More Voucher Codes → Tested and 100% Working | Take 50% off Young Chips at Iceland OR Score 50% off Pizza Orders |

| Sainsbury’s Discount Code – 70% Off in May 2024 | Tu Clothing Mega Sale! up to 60% off on Women’s Pyjamas! |

| Save 20% off | Next Discount Code & Vouchers | SAVE 20% on selected Denimwear |

What you are seeing here are examples of meta titles that suggest attractive, unlimited and widely available offers, when actually they are only available on very specific product categories or restricted to specific customers.

In the first example the meta title makes a user believe the 25% off is available to everyone, whereas the reality is it is only available if you’re lucky enough for it to be your birthday.

What’s notable is that you can always find an offer that has some semblance to the initial meta title but they are deals that, if they were presented in print form in a newspaper, for example, would be held up as misleading. At best they need to be heavily caveated, something that isn’t really feasible in web listings.

Implying a code exists when only on-site offers are listed happens 42% of the time:

The second type of misinformation that consumers looking for vouchers experience is when code sites imply that the prospective customer will get a voucher code when they click through to a ranking site. In instances where the meta title implies a voucher code is available, just 58% of them actually have a code to use. Here are some of the examples that make up the remaining 42% of meta titles:

What is the Meta Title | What is the actual Offer? |

| Wickes Discount Codes | 60% Off in May 2024 | Save up to 60% off orders in the clearance sale at Wickes |

| TUI Discount Code – £300 Off in May 2024 | Save £300 on 7 Night All-Inclusive Holiday at TUI BLUE Angora Beach in Izmir Area, Turkey |

| Tesco discount code 50% OFF in May 2024 | 50% off per kg of beef with Clubcard prices at Tesco |

| Sports Direct Discount Code – 90% Off | Save at Sports Direct – get Up to 90% off on Daily Deals |

| Screwfix Promo Code – 45% Off in May 2024 | Up to 45% off Sale on Selected Orders at Screwfix |

| adidas Discount Code – 50% Off | Up to 50% off Ozweego Outlet Range at adidas |

| Adidas Discount Codes – 25% off sale | We don’t currently have any Adidas deals. |

Here you can see examples of sites taking a very specific offer, positioning it as a widely available offer but also layering the idea of a discount code being available. So a user seeing ‘Wickes Discount Codes 60% off’ thinks they could get a discount code worth that value to use on their purchase when in reality this is just a generic clearance sale where no discount code is available.

These practices aren’t minor annoyances; they represent a systemic problem that undermines consumer trust and demonstrates what could be considered deceptive practices to attract eyeballs and clicks..

Given the Advertising Standards Authority is ramping up its scrutiny of online ads (and affiliate activity), is it only a matter of time before we see them stepping in to ensure consumers are better protected?

Are these practices the actions of a select few “Bad Actors”?

In our sample of 60 “brand + voucher code” searches, results spanned 30 different sites, with every voucher site featuring at least one vague or misleading offer. These misleading practices extend further; 80% of the voucher sites imply codes are available when the true nature of the offer is a generically available on-site saving.

It is noteworthy, that when you split these results by affiliate site, there are some sites who intentionally engage in these types of practices for every search position they rank for and others who attempt to avoid the problem altogether by rarely listing specific offers in their meta titles. The choice not to refer to specific offers in meta titles or meta descriptions, if adopted or enforced by the whole industry, is one that would certainly clean up consumer perceptions of the affiliate channel.

Some sites do already do this and it’s immediately clear how cleaner the user experience is and how well their expectations are set before they click through:

| What is the Meta Title | Meta Description |

| Loveholidays voucher codes | Find out more about our loveholidays voucher codes, and search for our best holiday deals. |

| British Airways Discount Codes & Vouchers | British Airways Discount Codes for July 2024 → Tested and 100% Working → Copy ✓ Paste ✓ Save. |

| John Lewis deals | Find the latest John Lewis discount codes & vouchers for July 2024. Use verified deals and save money on your favourite brands in the UK |

Both as a consumer and an affiliate marketer, I would love to see a change like this adopted in a more widespread way.

Are there other problems?

There are other areas we could also explore:

- Do meta titles and meta descriptions mention exclusive offers and do they really have them?

- Do meta titles, meta descriptions and snippets reference how many deals or codes they have and are those numbers accurate?

- Do codes listed on voucher sites actually work?

- Do the results change if you change the search term from “voucher code” to promo code or discount code?

I’ve not covered these because very often consumers are often looking for the best deal through generic search terms and the areas I’ve looked at are the most common starting points. What is clear is that they do not represent a consumer friendly experience for voucher hunters in the UK.

Do the search terms used sway the results?

In choosing which search terms to dive into, the top 60 were chosen based on the number of searches that they get each month from consumers across the UK and who operate an affiliate programme.

Therefore the results were primarily brand-based but if we were to speculate it would be that these figures might only get worse as the size of retailers and level of consumer diminishes..

How was this data collected?

Taking a sample size of 60 retailers, the top seven search results (420 total search results) and the full page of offers for each search result (around 4,500+ individual offers) were studied. The information collected included:

- Meta Titles

- Meta Descriptions

- Offer Titles on a voucher site’s brand page

- Offer Descriptions on a voucher site’s brand

- Wording used on the offer click through button

The meta titles and meta descriptions were collected using Serpapi.com and the offer titles and descriptions were collected using a web scraper called Octoparse.

How was this data analysed?

The collected data was categorised so that offers were segmented as either “offers” or “codes” and each meta title was compared against all possible offers to see which one was most alike to the initial meta title. This helped to answer a few fundamental questions that go right to the heart of the prospective customers’ experience such as:

- Do the meta titles reference specific offers, and are these offers available?

- When specific offers are mentioned, do those offers exist?

- When specific offers are mentioned in a meta title, are the terms clear?

- Do the meta descriptions imply there is an actual code to use?

- Is there a code to use (or an embedded code within the link)?

Conclusion

While we’ve all faced the frustration of hunting for valid voucher codes, the use of what could be deemed deceptive practices online is widespread. This study reveals that nine out of ten offers that lead us to voucher sites could be labelled unreliable and is an area the industry must address. If we don’t self-regulate, we could find an external body imposing stricter restrictions upon us; never the preferred outcome.

A crucial first step would be implementing stricter controls on the meta titles and descriptions consumers see when searching for offers. By working together as an industry and holding ourselves accountable, we can restore trust and credibility in the voucher space.

So the final question is, who can take the first step? Do brands consider adding this to their terms & conditions? Can affiliate networks adopt and enforce change on behalf of all their brands? Perhaps the APMA as an independent body can drive this change or in an ideal world, the affiliates themselves recognise this is a necessary change to adopt for the future of our industry. No matter who takes it on, one thing is clear – it has to change.

About the Author

Edwyn brings years of affiliate marketing experience and is the founder of Coam, an affiliate network dedicated to content only affiliate marketing. With a background that spans agencies, publishers, networks and a few personal sites too, Edwyn has a unique insight into the industry’s inner workings and knows first hand how SEO & Affiliate Marketing interlink.